Historical Roots of Deep Philosophy

The Deep Philosophy Group was founded in 2017, but its historical roots are much older. We are part of the long historical discourse of Western philosophers, and we have been inspired by many important thinkers:

Plato (427-347 BC): This great ancient Greek philosopher tells us that philosophy is motivated by “Eros” – love or yearning. In Deep Philosophy we take from him the insight that as humans beings we are normally imprisoned in our narrow “cave,” and that philosophy can help us step out of our cave to connect with higher dimensions of understanding and of realness. Philosophy, then, is a path of elevating life.

Plato (427-347 BC): This great ancient Greek philosopher tells us that philosophy is motivated by “Eros” – love or yearning. In Deep Philosophy we take from him the insight that as humans beings we are normally imprisoned in our narrow “cave,” and that philosophy can help us step out of our cave to connect with higher dimensions of understanding and of realness. Philosophy, then, is a path of elevating life.

Marcus Aurelius (121-180 AD): This Stoic philosopher wrote his profound Meditations as a personal notebook of philosophical-spiritual exercises. We take from him the understanding that philosophy is a way of life which involves ongoing contemplation on the foundation of life and the world. The task of philosophy is to liberate us from our automatic psychological forces, and to help awaken our deeper self, or what he calls “the guiding principle” (the “daemon”) within us. In this way philosophy helps create inner change and self-transformation towards harmony with reality (the “cosmos”).

Marcus Aurelius (121-180 AD): This Stoic philosopher wrote his profound Meditations as a personal notebook of philosophical-spiritual exercises. We take from him the understanding that philosophy is a way of life which involves ongoing contemplation on the foundation of life and the world. The task of philosophy is to liberate us from our automatic psychological forces, and to help awaken our deeper self, or what he calls “the guiding principle” (the “daemon”) within us. In this way philosophy helps create inner change and self-transformation towards harmony with reality (the “cosmos”).

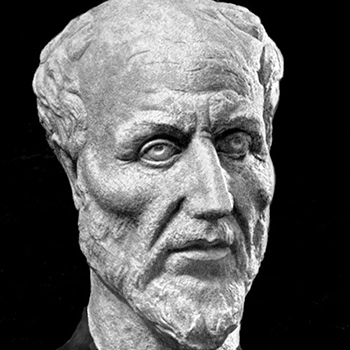

Plotinus (204–270 AD): According to this major Neo-Platonic philosopher, meditative thinking and intuitive understanding can help us transcend our ordinary self and take part in the higher levels of reality for which we yearn. In Deep Philosophy we share with him the vision that meditative (or contemplative) philosophy can help us elevate or deepen ourselves and get in touch with the fullness of reality.

Plotinus (204–270 AD): According to this major Neo-Platonic philosopher, meditative thinking and intuitive understanding can help us transcend our ordinary self and take part in the higher levels of reality for which we yearn. In Deep Philosophy we share with him the vision that meditative (or contemplative) philosophy can help us elevate or deepen ourselves and get in touch with the fullness of reality.

Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494): For this Italian philosopher of the Renaissance, philosophy is a way to transform and elevate ourselves to higher dimensions of life. We also share with him the idea that different philosophies are not necessarily contradictory, but are different aspects of a common wisdom. This is why we can contemplate on different philosophical texts and treat them as different voices from the rich human symphony.

Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494): For this Italian philosopher of the Renaissance, philosophy is a way to transform and elevate ourselves to higher dimensions of life. We also share with him the idea that different philosophies are not necessarily contradictory, but are different aspects of a common wisdom. This is why we can contemplate on different philosophical texts and treat them as different voices from the rich human symphony.

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592): This French Renaissance philosopher wrote his “Essays” by weaving together anecdotes and personal stories, quotations from ancient thinkers, and his own philosophical insights and ideas. We share with him the understanding that philosophical ideas need not be separate from everyday life. Life and philosophy can be woven most intimately together.

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592): This French Renaissance philosopher wrote his “Essays” by weaving together anecdotes and personal stories, quotations from ancient thinkers, and his own philosophical insights and ideas. We share with him the understanding that philosophical ideas need not be separate from everyday life. Life and philosophy can be woven most intimately together.

Benedict Spinoza (1632-1677): According to this Jewish Dutch philosopher, the study of philosophy can cultivate a higher state of mind and wisdom (“the third kind of knowledge”) which involves joy, virtue, and love of the world. We share with Spinoza the idea that the highest level of philosophical understanding is not only a matter of possessing abstract ideas, but also expanding our mind to connect with the wholeness of reality.

Benedict Spinoza (1632-1677): According to this Jewish Dutch philosopher, the study of philosophy can cultivate a higher state of mind and wisdom (“the third kind of knowledge”) which involves joy, virtue, and love of the world. We share with Spinoza the idea that the highest level of philosophical understanding is not only a matter of possessing abstract ideas, but also expanding our mind to connect with the wholeness of reality.

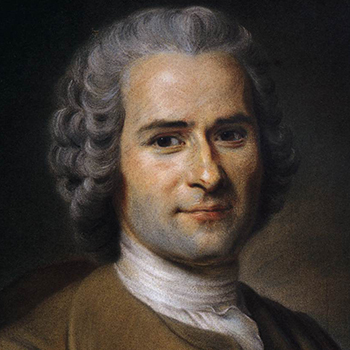

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778): The Swiss-French philosopher Rousseau distinguishes between the true self (or “natural self”) and the superficial mask which we normally wear without being aware of it, and which is a product of psychological and sociological forces. In Deep Philosophy we take from Rousseau the task of going beyond our psychological patterns to reconnect with the original, deeper dimension of ourselves.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778): The Swiss-French philosopher Rousseau distinguishes between the true self (or “natural self”) and the superficial mask which we normally wear without being aware of it, and which is a product of psychological and sociological forces. In Deep Philosophy we take from Rousseau the task of going beyond our psychological patterns to reconnect with the original, deeper dimension of ourselves.

Novalis (1772-1801): From this philosopher and poet of German Romanticism, we receive the idea that philosophy can be practiced in the togetherness of a group. When each participant contributes his own partial thought, the discourse becomes a rich polyphony of ideas that is greater than its parts. Novalis and his colleagues call this philosophy-in-togetherness “Symphilosophy.” We also take from him the ideas of an inner source of higher wisdom within us, and of the deep connection between philosophical and poetic thinking.

Novalis (1772-1801): From this philosopher and poet of German Romanticism, we receive the idea that philosophy can be practiced in the togetherness of a group. When each participant contributes his own partial thought, the discourse becomes a rich polyphony of ideas that is greater than its parts. Novalis and his colleagues call this philosophy-in-togetherness “Symphilosophy.” We also take from him the ideas of an inner source of higher wisdom within us, and of the deep connection between philosophical and poetic thinking.

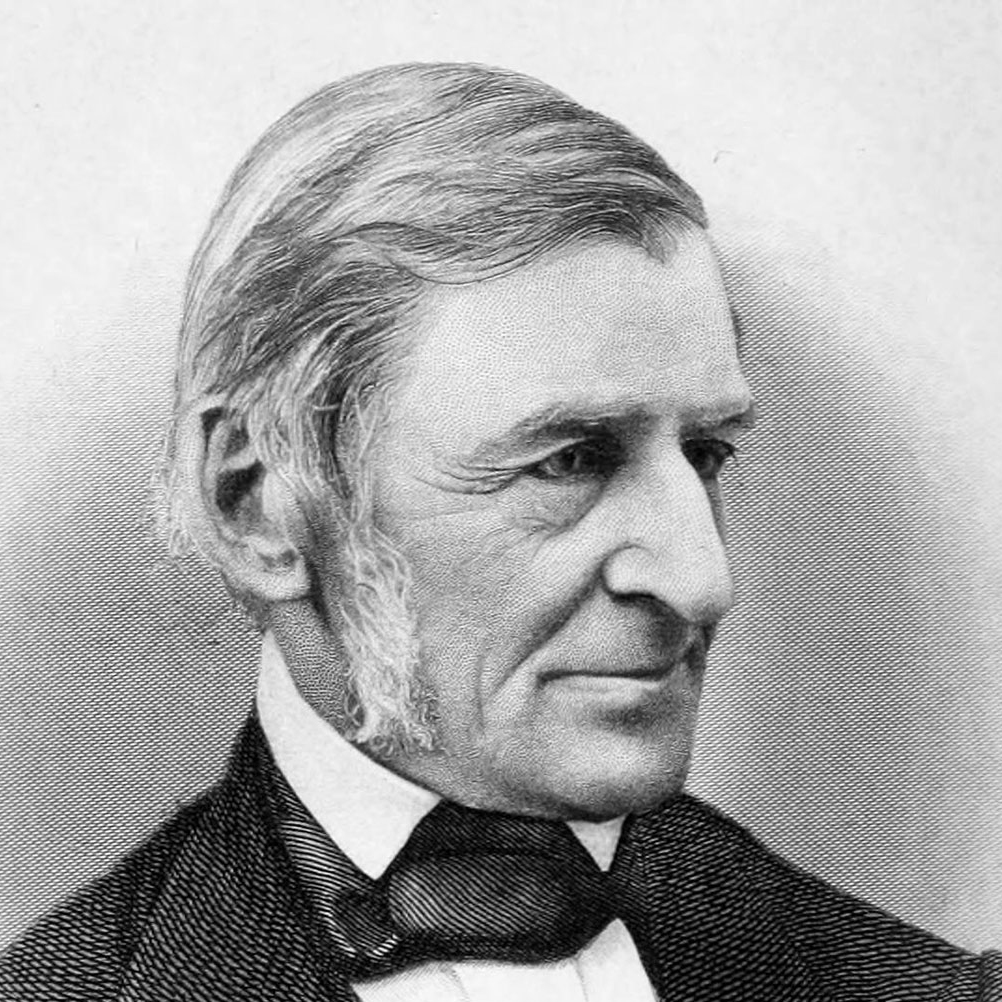

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882): Emerson, leader of American Transcendentalist philosophy, teaches us about the “over-soul” – a source of creative insights and inspiration that is beyond our normal self and our normal understanding. In Deep Philosophy we take from him his call to open ourselves inwardly to this fountain of inspiration and wisdom, so that we can receive form it new unexpected ideas and insights.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882): Emerson, leader of American Transcendentalist philosophy, teaches us about the “over-soul” – a source of creative insights and inspiration that is beyond our normal self and our normal understanding. In Deep Philosophy we take from him his call to open ourselves inwardly to this fountain of inspiration and wisdom, so that we can receive form it new unexpected ideas and insights.

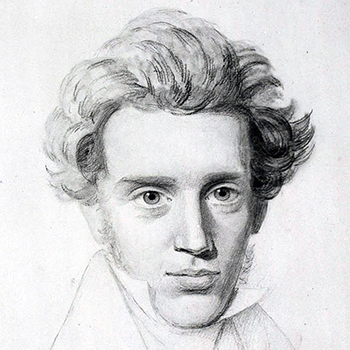

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855): For Kierkegaard, the Danish philosopher and father of Existentialism, the individual’s struggle with basic life-issues cannot be separated from concrete life. Objective theories are not enough, because truth is a matter of one’s personal attitude, commitment, and choice, and it requires self-awareness, authenticity, and seriousness. In Deep Philosophy we share with Kierkegaard the idea that philosophical thinking is intimately connected to one’s personal relationship with life.

Søren Kierkegaard (1813-1855): For Kierkegaard, the Danish philosopher and father of Existentialism, the individual’s struggle with basic life-issues cannot be separated from concrete life. Objective theories are not enough, because truth is a matter of one’s personal attitude, commitment, and choice, and it requires self-awareness, authenticity, and seriousness. In Deep Philosophy we share with Kierkegaard the idea that philosophical thinking is intimately connected to one’s personal relationship with life.

Henri Bergson (1859-1941): The French philosopher Bergson asks us to examine our deep inner experiences and realize that they cannot be analyzed or even described with precision. In Deep Philosophy we share with him the insight that our inner life cannot be captured with theoretical thinking. To appreciate our inner depth we need another form of understanding, one that is holistic, attentive, pre-linguistic, or what he called “intuition.”

Henri Bergson (1859-1941): The French philosopher Bergson asks us to examine our deep inner experiences and realize that they cannot be analyzed or even described with precision. In Deep Philosophy we share with him the insight that our inner life cannot be captured with theoretical thinking. To appreciate our inner depth we need another form of understanding, one that is holistic, attentive, pre-linguistic, or what he called “intuition.”

Martin Buber: (1878-1965): According to this Jewish Austrian-Israeli philosopher, the foundation of human reality is relationships to others, not individual selves. Togetherness with others, with nature, and even with the voices of already-dead thinkers is necessary in order to connect to the depth of human reality. In Deep Philosophy we take from Buber the power of thinking in togetherness, and the possibility of resonating in togetherness with our companions and with historical thinkers.

Martin Buber: (1878-1965): According to this Jewish Austrian-Israeli philosopher, the foundation of human reality is relationships to others, not individual selves. Togetherness with others, with nature, and even with the voices of already-dead thinkers is necessary in order to connect to the depth of human reality. In Deep Philosophy we take from Buber the power of thinking in togetherness, and the possibility of resonating in togetherness with our companions and with historical thinkers.

Karl Jaspers (1883-1969): This German existentialist philosopher (and psychiatrist) reminds us that our thinking tends to objectify the world, and it is therefore blind to the primordial reality that is more basic than objects and objectification. However, philosophical texts (as well as poetry, nature, myth) can act as “ciphers” that point us towards this pre-objective primordial reality. In Deep Philosophy we take from Jaspers the understanding that philosophical ideas can serve not just as theories about the world of objects, but as ciphers that take us beyond the limits of objective thinking. We also take from Jaspers his view that the philosophical life allows us to recollect ourselves from being lost in our everyday activities.

Karl Jaspers (1883-1969): This German existentialist philosopher (and psychiatrist) reminds us that our thinking tends to objectify the world, and it is therefore blind to the primordial reality that is more basic than objects and objectification. However, philosophical texts (as well as poetry, nature, myth) can act as “ciphers” that point us towards this pre-objective primordial reality. In Deep Philosophy we take from Jaspers the understanding that philosophical ideas can serve not just as theories about the world of objects, but as ciphers that take us beyond the limits of objective thinking. We also take from Jaspers his view that the philosophical life allows us to recollect ourselves from being lost in our everyday activities.

Paul Tillich (1886-1965): According to this German-American thinker, texts and ideas can function as “symbols” that take us beyond themselves and beyond factual description. We take from Tillich the understanding that philosophical texts and ideas can function as such symbols, if we open ourselves to them. They can open for us hidden levels of realities that cannot be accessed in any other way, and also open us to those realities.

Paul Tillich (1886-1965): According to this German-American thinker, texts and ideas can function as “symbols” that take us beyond themselves and beyond factual description. We take from Tillich the understanding that philosophical texts and ideas can function as such symbols, if we open ourselves to them. They can open for us hidden levels of realities that cannot be accessed in any other way, and also open us to those realities.

Gabriel Marcel (1889-1963): For this French existentialist philosopher, a central dimension of human life is “mystery” – a personal reality that cannot be captured from the perspective of an objective observer. We can appreciate the “mystery” element of our life by experiencing it personally and living it authentically, but not by theorizing about it intellectually. In Deep Philosophy we take from Marcel the understanding that the deep personal dimension of our being cannot be accessed through intellectual thinking alone. It requires our entire being, and our authentic self-reflection.

Gabriel Marcel (1889-1963): For this French existentialist philosopher, a central dimension of human life is “mystery” – a personal reality that cannot be captured from the perspective of an objective observer. We can appreciate the “mystery” element of our life by experiencing it personally and living it authentically, but not by theorizing about it intellectually. In Deep Philosophy we take from Marcel the understanding that the deep personal dimension of our being cannot be accessed through intellectual thinking alone. It requires our entire being, and our authentic self-reflection.

Maria Zambrano (1904-1991): This Spanish philosopher developed a special poetic language of thought to explore aspects of experience that lie beyond theoretic thinking. We take from her the understanding that we need to open within us a special inner space, or “clearing in the forest,” in order to receive transformative insights of deep hidden levels of life and reality. For Deep Philosophy this means the importance of poetic thinking, quiet contemplation, and inner listening.

Maria Zambrano (1904-1991): This Spanish philosopher developed a special poetic language of thought to explore aspects of experience that lie beyond theoretic thinking. We take from her the understanding that we need to open within us a special inner space, or “clearing in the forest,” in order to receive transformative insights of deep hidden levels of life and reality. For Deep Philosophy this means the importance of poetic thinking, quiet contemplation, and inner listening.